Kiwis’ love-hate relationship with agapanthus

Nelson should consider following Auckland in banning the weedy forms of agapanthus, an expert in the plant says.

Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research botanist Murray Dawson has spent the best part of a decade breeding sterile agapanthus as part of the Agapanthus Research Group. At present, seed set trials are going on in three locations: the Christchurch Botanic Gardens, the Auckland Botanic Gardens, and Pukekura Park in New Plymouth.

By changing chromosome numbers, Dawson was able to create low-fertility or sterile cultivars such as Rachel and Kath, named after technical experts Kath Stewart and Rachel Innes for their help with the project.

Rachel, for instance, produces one or two seeds per plant annually compared with other varieties that spawn some “tens of thousands” of seeds each.

Dawson sees this as a win-win as gardeners can still grow the plants they enjoy but without the weedy proclivities that have caused them to fall out of favour, particularly with people who have broken shovels or perhaps their backs when attempting to remove them.

It has been suggested that agapanthus should be added to the National Pest Plant Accord, but Dawson would prefer they were dealt with on a location-by-location basis and included in regional pest management strategies instead.

In coastal areas such as Auckland, with a higher rainfall and warmer climate, agapanthus disperse readily. In Canterbury, they still grow well but conditions are not so amenable for the plant to become weedy.

The Auckland Regional Council banned the sale, propagation, and distribution of large growing forms of agapanthus in 2008, while the Bay of Plenty Regional Council classifies agapanthus as a restricted pest plant.

In Nelson, the ubiquitous South African native can be spotted all over the city, holding up steep banks, on riversides and adorning yards – and it was here, and in areas such as Westland, where they “should probably be banned”, Dawson said.

Asked where he sat with the African lily, Dawson said he could see both perspectives. They were hard to grow in cooler regions of North America and Europe, and there was even a specialist agapanthus fertiliser available in the United Kingdom, but in New Zealand no care was required whatsoever.

“There’s a wee bit of a case of familiarity breeds contempt,” he said.

Back in their heyday in the 1980s and 1990s, the plants were a million-dollar export earner, and New Zealand was known as the country that produced the most selections, some 80 cultivars out of more than 600 worldwide. Some cultivars to this day are grown for international trade.

They have other redeeming features too, as their succulent leaves make them fairly fire resistant and they stabilise innumerable banks, Dawson said.

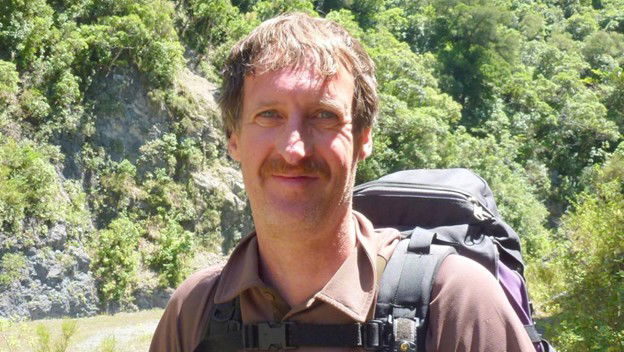

Botanist Murray Dawson says there may be a case of “familiarity breeds contempt” when it comes to the ubiquitous agapanthus. SUPPLIED

Professor Margaret Stanley, an ecologist at the University of Auckland, said it was the agapanthus’ underground corms, which stored carbohydrates for the plant, that made them so difficult to remove.

“You can kind of cut off the top, but they will keep growing back,” she said.

The plants outgrow others, becoming a “big monoculture”, particularly in areas with a lot of light, by forming stands that crowd out coastal herbs, shrubs and grasses and the insects, lichen and birds associated with them.

Stanley suggested the rengarenga as a native plant with the same form as an alternative.

Dr Chris Phillips, a senior researcher at Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research specialising in how vegetation is used to manage erosion, said that as a general principle, he wouldn’t be promoting a pest plant when another plant, be it exotic or native, could perform the functional role required.

“Even though it has been observed in the past that these things work, we shouldn’t do it,” he said. “It’s a weed.”

Eco-friendly, less invasive cultivars that have passed low-fertility tests can be found on the Auckland Botanic Gardens website.

By Catherine Hubbard, Nelson Mail

This Post Has 0 Comments